Written by FTMA’s Kat Welsh

Lift Off on Test Mission to Reduce Mounting Space Debris

When the Wright brothers started designing the first plane, probably many people thought they were batshit, despite the fundamental desire of flight dating back centuries. Leonardo Da Vinci made more than 500 sketches and designs conceptualising human flight.

Yet, December 13th, 1903, Orville and Wilbur made history – their first powered flight lasted 12 seconds, with the best test flight of the day lasting 59 seconds and covering 255.6m.

Guess what the plane was made out of? Wood, muslin, and an aluminium engine.

In the 1940’s, tasked with building large scale troop and military transports, Howard Hughes designed and built an aircraft that still holds world records today. It could not be made out of aluminium due to government wartime restrictions. Turning to readily available materials, The H-4 Hercules, or the Spruce Goose, was entirely – aside from the engine – made out of Duramold, a laminated birch and poplar plywood. The H-4 Hercules is still the largest sea plane, and largest plane ever to be built out of wood.

H-4 Hercules, aka the Spruce Goose. Photo credit: Evergreen Aviation and Space Museum.

In 1903, there was one plane that took off that famous day. Fast forward 121 years, and the average number of commercial flights per day is 101,842. The materials used to build planes is a far cry from the grassroots of the Wright brothers and the restrictions on Howard Hughes. These days our airspace is filled with crafts, spaceships, and satellites, constructed with aluminium and titanium alloys, glasses, polymers, plastics, and more. At end-of-life for the average Airbus, there are possibilities for deconstruction and recycling – but for anything leaving the atmosphere, there is a hitch.

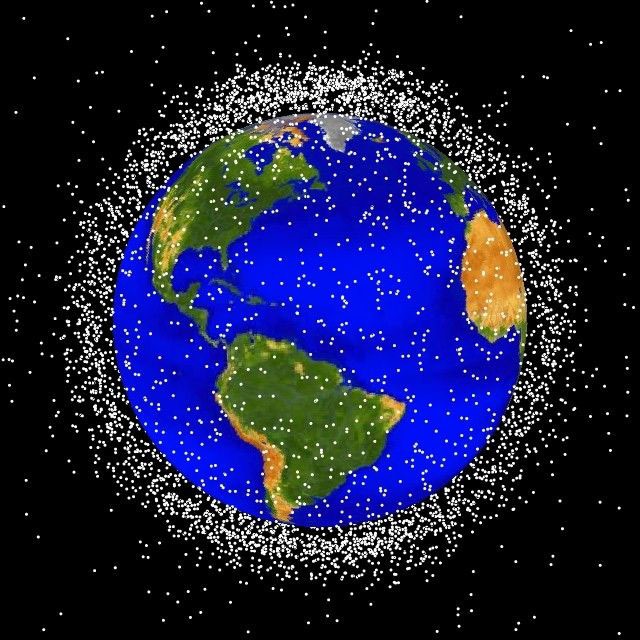

Little known is how much space ‘waste’ floats in our Low Earth Orbit (LEO) due to defunct wreckages from the interstellar industry. If we thought landfill on Terra was terrible, it’s just ground zero – our LEO is packed with scrap.

‘There are no international space laws to clean up debris in our LEO. LEO is now viewed as the World’s largest garbage dump, and it’s expensive to remove space debris from LEO because the problem of space junk is huge – there are close to 6,000 tons of materials in low Earth orbit… Space junk is no one countries’ responsibility, but the responsibility of every spacefaring country. The problem of managing space debris is both an international challenge and an opportunity to preserve the space environment for future space exploration missions.’ (NASA’s ‘Space Debris’).

Nasa’s CGI image depicting how much space debris orbits earth – ‘Most orbital debris comprises human-generated objects, such as pieces of space craft, tiny flecks of paint from a spacecraft, parts of rockets, satellites that are no longer working, or explosions of objects in orbit flying around in space at high speeds.’

We need to clean up our act – not just around our feet but around our heads too.

Space waste may be out of sight for most of us, but for some, it most definitely isn’t out of mind. A pioneering trial for the future of satellites is going back to basics to tackle this problem.

While FTMA is promoting the benefits that nature can provide, aka sustainable forestry to reduce the impact of global emissions, it turns out that maybe mother nature can help out with our cosmic concerns too.

After having its commercial air travel plans grounded in place of ‘modern’ materials, wood, as it turns out has had its flight status rescheduled.

On the 4th November, LignoSat – the world’s first wooden satellite developed by Japanese scientists – hitched a ride aboard an unmanned SpaceX flight from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida. It’s now safely at the International Space Station, soon to embark on its maiden voyage to test timber out in space.

The thoughts behind it? On re-entry at the end-of-life, rather than contribute to the debris fields, it will burn up and not compound problems further.

‘With timber, a material we can produce by ourselves, we will be able to build houses, live and work in space forever,’ said Takao Doi (Astronaut who has flown on the Space Shuttle and studies human space activities at Kyoto University). With a 50 year plan of planting trees and building timber houses on the moon and Mars, Doi’s team decided to develop a NASA-certified wooden satellite to prove wood is a space-grade material. (Reuters). ‘Metal satellites might be banned in the future,’ Doi said. ‘If we can prove our first wooden satellite works, we want to pitch it to Elon Musk’s SpaceX.’

Their vision is inspiring, whilst using resources that are sustainable, and looking to nature for answers. The satellite is made from honoki, a type of magnolia wood native to Japan which traditionally is used to make sword scabbards. This type of wood is highly durable and shatter resistant. The plan for LignoSat is to orbit earth for 6 months, whilst sensors collect data on how it is holding up in space. Wood’s natural nemesis’ (water / fire) won’t be bothering it, but it will need to endure rapid temperature changes ranging from -100 to 100 degrees Celsius every 45 minutes, as it traverses between sunlight and darkness.

‘While some of you might think that wood in space seems a little counterintuitive, researchers hope this investigation demonstrates that a wooden satellite can be more sustainable and less polluting for the environment than conventional satellites,’ Meghan Everett (Deputy Chief Scientist for NASA’s International Space Station program) said in a press briefing on 4th November.

As we reach a crucial moment in the planet’s ability to support its growing human population, we have to embrace any solution that involves sustainable renewables, promotes circular economies, and still advances progressiveness.

Sometimes the biggest conundrums, have the simplest solutions.

Watch this space, literally, to see how far the timber industry might be expanding in the future – the stars are not the limit.

Follow FTMA Australia for Industry News and Updates

Our Principal Partners